Genes, Gods and Collapse

How DNA is revealing the secrets of the Maya — and what prehistoric genomes tell us about continuity

A Realm of Limestone and Chromosomes · AmazingTemples.com, July 2025

“Bones don’t lie — but they need scientists to make sense of them.”

Recent archaeogenomic work is reshaping our picture of the Maya. In a sealed sacrificial cave at Chichén Itzá, researchers sequenced 64 children’s skeletons (AD 500–900): all were male, many were brothers or even twins—a biological echo of the Hero Twins myth. Meanwhile, seven genomes from Copán reveal a marked influx of central-Mexican DNA from about AD 400, exactly when the “foreign ruler” K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ appears in inscriptions.

PSMC models show the population curve climbing until AD 730, then plunging around 750—the same collapse archaeologists trace in abandoned palaces and unfinished monuments. After 1500, imported diseases further selected protective HLA variants that are now over-represented among today’s Maya.

Still unclear is how southern centers like Tikal or Calakmul fit this picture; Preclassic DNA could reveal whether the earliest pyramid builders were direct ancestors of the Classic dynasties. Functional genomics and cross-checks with ceramics and texts promise deeper insights—each new sample is another puzzle piece binding history, biology, and myth ever more tightly together.

A leap through time and water

Picture this: the midday sun blazes over Yucatán. A cenote yawns at your feet, a thousand-year-old sacrificial well of the Maya. In nearby caves such as the Chultún of Chichén Itzá, archaeogeneticists are now recovering the most precious commodity: DNA. Only in the airtight sediment layers of these caves has genetic material survived — a stroke of luck for science.

Important: The genome study analysed samples from a sealed sacrificial cave (Chultún) next to the Sacred Cenote. Cenotes themselves rarely preserve DNA in the tropics, yet their symbolic role as holy water places remains central.

A whiff of copal rises, mingling with the jungle’s humidity …

The voice of the genes: new studies revolutionise our understanding

| Year / Site | Publication | Core findings |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 – Chichén Itzá (Mexico) | Nature | • 64 genomes from children’s skeletons (AD 500–900) • All genetically male, including twin pairs • Local recruitment for sacrificial rituals • Continuity with today’s Maya, but shifts in HLA alleles |

| 2025 – Copán (Honduras) | Current Biology study (July 2025) – abstract via ScienceDirect | • 7 genomes from the Classic Period • Influx of Mexican genes from AD 400 • Population peak AD 730 • Sharp decline from AD 750 • Summaries: LiveScience, SciTechDaily, The Guardian |

Ritual practice & society

DNA from the Chichén Itzá Chultún shows that virtually all victims were children and male — sacrificial boys — and many were brothers or cousins; two pairs of identical twins were even identified. These “boy groups” mesh strikingly with figurines and painted ceramics that depict adolescent males in sacrificial scenes. Maya specialists immediately recall the Hero-Twins myth from the Popol Vuh: two brothers descend into the underworld to be sacrificed. Genetics thus supplies biological proof for the archaeological finds and finally dispels the older idea that girls were the primary cenote victims.

Migration & state formation

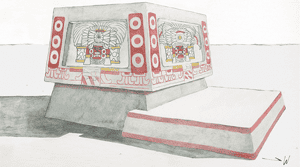

The Copán genomes reveal that around AD 400 DNA sequences appear that had previously been found almost exclusively in Central Mexico. Hieroglyphs date the coronation of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ — the legendary “foreign ruler” — to this same period. Inscriptions and genes alike therefore point to real immigration: families from Mexico settled in Copán, intermarried, and founded a new dynasty. Archaeologists note matching Teotihuacán-style building techniques on the Acropolis.

Demography & collapse

PSMC models, which back-calculate past population size from fragmented DNA, paint a stark picture: around AD 730 the Maya population peaks; just twenty years later, circa 750, the curve plunges. The genomes show no outside conquest — the same genetic stock persists, simply in much reduced numbers. Droughts, political strife, and crop failures likely combined to trigger this dramatic contraction — the biological signature of the political-ecological collapse visible in abandoned palaces and halted monument works. It is a sharp demographic crash, not a wholesale population replacement like the Bronze-Age steppe migrations of Europe.

Adaptation to disease

Certain immune-system genes (HLA, including DRB104:07*) occur far more often among modern Maya than chance predicts. Evolutionary biologists see the unmistakable “fingerprint of selection”: after Europeans introduced smallpox, measles, and other infections, carriers of versions that recognised those pathogens survived at higher rates. Within a few generations the protective variants spread — a textbook example of disease reshaping both history and genome.

The echo of a conch shell rolls across the temple plaza …

Lab magic: how researchers make Maya DNA speak

A lay tour of the aDNA lab

- Treasure hunt in the bone

- Pars petrosa — the densest cranial bone, a natural DNA safe.

- Tooth roots — hard shell, hollow core still rich in vessel DNA.

- Bones come from sealed ritual chambers with charred offerings: secure dating, clear context.

- Sterile ballet in the clean room

- Grind off surfaces, UV-bathe to kill microbes.

- Full-body suits prevent human skin cells from intruding.

- Pulverise, lyse — the bone becomes DNA “tea”.

- Building a library

- UDG treatment smooths age damage (C→T).

- Barcode adaptors tag every fragment.

- Result: a picogram-sized “book” ready for sequencing.

- Hybrid capture

- Instead of reading the whole genome repeatedly, researchers fish out 1.24 million diagnostic SNPs—pulling marked pages from an archive to save time and cost.

- Authenticity checks

- Deamination “rust” at fragment ends.

- Male bones with too much XX hint at contamination.

- Only when all lights are green does the dataset count.

- Math, not microscope

- PCA plots = ancestry graphs.

- ADMIXTURE bars = colour-coded gene cocktails.

- qpAdm = calculator for “how much Mexican vs. local” in Copán.

- Archaeologists and geneticists in dialogue

- Radiocarbon stamps time.

- Stable isotopes reveal diet.

- Community reviews with Maya representatives ensure the work isn’t a colonial project.

Fireflies trace glowing lines through the dusk …

Collapse and continuity

Between AD 750 and 950 royal names vanish from stelae, palaces go unrepaired, pyramid building halts. Archaeologists find rushed trash fills where neat construction offerings once lay — a sure sign of exhaustion. DNA tells the same story from the inside: the hereditary substance is unchanged, but the number of carriers plummets. The Maya do not disappear — their kingdoms implode.

The sweet scent of fermented cacao hangs in the air …

Where research leads — open questions in Maya genetics

- Geographical gaps — blank spots on the genome map

- Missing: southern lowland centres Tikal, Calakmul, many Belize sites.

- Why exciting? They differ politically and architecturally; genetics might show whether biology matches those differences.

- Functional genomics — genes that act

- Beyond ancestry: which genes were active (immunity, metabolism, altitude tolerance)?

- Could rising malaria-resistance genes align with pollen data for standing-water settlements?

- Temporal depth — back to the Preclassic (< 1000 BC)

- DNA elusive, but even a few early genomes could show if the first pyramid builders were ancestors of later dynasties.

- Cultural genomics — DNA as another chapter of the chronicle

- Align genetic clades, texts, ceramic styles.

- Example: Teotihuacán talud-tablero style in Copán coincides with Mexican-inflected DNA; similar cross-checks might crack the jade-trade or “chocolate route” puzzles.

Take-away for hobby researchers: archaeogenetics rarely gives final answers, but sharply narrows the possibilities. Each new sample is a puzzle piece forcing art historians, linguists, and archaeologists to rethink familiar narratives.

Access to the sources

Open access

- Nature-Artikel (Chichén Itzá) — full methods

- Current Biology-Studie (Juli 2025) zur Copán-DNA – abstract via ScienceDirect

Einführungen:

- LiveScience: mythic background

- SciTechDaily: technical innovations

- The Guardian: cultural significance

Quick takeaway

The latest genome studies paint a nuanced portrait: the Classic Maya experienced migration, crises, and adaptation, but they never vanished. New lab techniques now unlock even heavily degraded tropical DNA, opening a fresh chapter in Maya research.