The Long Farewell: Why the Classic Maya Civilization Collapsed

Introduction

When we hear the word “collapse,” we often imagine crumbling pyramids and panicked people fleeing. Yet archaeological evidence reveals a far more nuanced story. Between roughly 750 and 950 CE, the great royal courts of the southern lowlands—such as Tikal and Copán—dissolved within a few generations. Meanwhile, cities farther north, like Uxmal, and later Chichén Itzá, experienced a renaissance.

This staggered transformation across time and space resulted from a complex convergence of environmental, economic, and political crises. In the following sections, I trace this process, contextualize firmly established findings, and highlight areas where scholarly debate remains open. Section 6 concludes with a Maya perspective, showing how contemporary indigenous communities interpret the so-called “collapse” and the cultural continuities they emphasize.

1 | Apex of the Classic Maya

During the Classic Period (approximately 250–900 CE), Maya cities emerged from the lowland jungle like stone chronicles. Monumental stelae recorded dynasties, wars, and alliances; hieroglyphic staircases celebrated victories; astronomers calibrated calendars to align celestial events with ritual dates.

At the same time, sophisticated water‑management systems—including reservoirs, terrace fields, and canal networks—ensured cultivation of maize, beans, and squash even during droughts.

Trade routes, sometimes elevated and paved—known as sacbéob—connected cities, while rivers and coastal waters carried jade from the Motagua Valley, fine Pachuca obsidian from central Mexico, and marine salt from northern lagoons deep into the rainforest.

All this formed the material basis of the monumental culture that still enthralls visitors today.

2 | Decline in Time and Space

2.1 How the Monuments Fell Silent

Hieroglyphic stelae with Long Count dates provide a window into the past, allowing precise chronology.

The following table shows when key centers fell silent:

| Phase | Sites & Last Long Count | Secure Date | Core Literature | Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Silence | Coba, Palenque, Copán | 9.18.0.0.0–9.18.12.6.9 (780–822 CE) | Monuments 1, 9, 10 | Coba stelae eroded; possibly 9.19.0.0.0 (~810) |

| Middle Stage | Caracol, Tikal | 10.2.0.0.0–10.2.10.0.0 (859–869 CE) | K’atun stelae & temple lintels | – |

| Late Afterglow | Uxmal, Calakmul, Toniná | 10.3.0.0.0–10.4.0.0.0 (890–909 CE) | Toniná Monument 101 | – |

| Last Flicker | Chichén Itzá | 10.7.0.0.0 (998 CE) | Graña‑Behrens 1999 | – |

A clear pattern emerges: the silence of the monuments spreads from south to north. The farther toward the Puuc hills and northern coast one goes, the longer the Long Count tradition persisted.

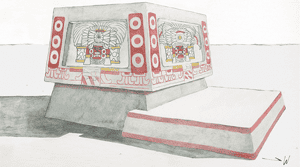

This drawing depicts Stela H. It is of Waxaklahun-Ubah-K’awil in the role of the Maize God. Source: Linda Schele & Peter Mathews, The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs, p. 154

2.2 Archaeological Snapshots

Visitors to abandoned Maya cities often see staircases abruptly ending halfway up, or overgrown lime kilns with unused fuel still in place. Whether these indicate sudden building halts or ritualized incompletion remains debated on a case-by-case basis.

LiDAR data shows that as city centers were depopulated, secondary settlements on the margins sometimes grew—suggesting a decentralized retreat pattern reminiscent of other crisis moments.

Luxury goods tell a story too: in Copán, the number of jade offerings drops sharply, while in Kiuic, in northern Puuc, substantial quantities of Pachuca obsidian are present even after 900 CE. This indicates luxury trade did not entirely vanish but sought new, more resilient channels.

2.3 The Silence Map

Combining epigraphic and ecological data paints what looks like a relay collapse:

- In the southern lowlands, drought, warfare, and emigration combine—monuments fall silent before 830 CE.

- The central lowlands struggle on; K’atun festivals continue until about 869 and then end.

- In the Puuc region, cenote reservoirs, managed aguadas, and new coastal trade routes afford a 20–40‑year reprieve.

- Finally, Chichén Itzá, with its position on maritime corridors (and possible Toltec alliances), becomes the last major site with Long Count inscriptions.

2.4 Logistics as a Thread of Fate

Why did monumental programs fade alongside luxury imports? The answer lies in era-dominating supply chains. The collapse of vital everyday goods flows proved fatal: without salt from Yucatán (for food preservation), chert from Belize (for tools), or obsidian from Guatemala, local provisioning broke down. In Copán, obsidian availability dropped by 90% (Hirth 2020), while sites like Tulum survived longer thanks to maritime fisheries. It was not luxury trade but the loss of daily essentials that doomed the court system.

The northern coast, in contrast, appears (according to ethno‑historical sources) to have innovated large oceangoing canoes, enabling jade, obsidian, and Plumbate ceramic to arrive by sea across the Gulf of Mexico. As long as that maritime artery pulsed, rulers at Uxmal or Chichén Itzá could still carve their authority in stone.

3 | Multi-layered Causes

3.1 Climate Drift

Stalagmites from Yok Balum and Tzabnah function like climate diaries. Their oxygen isotope records show roughly 50‑year-scale abrupt drought spikes. Lake sediments from Chichancanab reflect the same patterns, reinforcing their reliability.

3.2 Environment and Resources

Pollen diagrams reflecting high emissions from lime kilns reveal a shift from tree pollen to maize and grass taxa. This indicates deforestation, soil erosion, nutrient depletion, and dropping groundwater levels worsening supply constraints.

3.3 Power and Violence

Prolonged wars destabilized resources and undermined politics. The famous Tikal–Calakmul “Star Wars” conflict (~560–800 CE) forced tributary burdens on allies like Naranjo or Caracol. Archaeobotanical evidence shows that during intense conflict phases (e.g., 695–726 CE), the protein content in Tikal skeletons dropped by 30%—a direct sign of famine from agricultural disruption and labor diversion. As crisis deepened, triumphant inscriptions fade; alliance formulas and genealogies rise—a sign that elites sought new forms of legitimacy as war became more costly.

3.4 Tribute and Inequality

Some texts—like Stela D from Copán—complain of rising tribute levels. Though not universal, these fit with archaeological signs of condensed ceremony centers and thinned peripheries.

3.5 Trade Disruptions and New Networks

Luxury trade dwindled in the south, but in the north Plumbate ware and fine orange ceramics flourished well past 910 CE. A notable find is a sintered Plumbate bowl from Isla Cerritos, with petrographic signatures tying it to the Soconusco coast—proof that maritime trade carried luxury goods over 1,000 km long after the southern collapse. Old arteries clogged; new capillaries opened.

3.6 Water as Achilles’ Heel

Hydrological models of Tikal’s reservoirs show that sustained droughts cause the fresh-water table to fall below access limits. The result: crop failure, pilgrim decline, collapse in revenue—a cascade of consequences critical to elite institutions.

3.7 A Mosaic of Stressors

Population booms, Ilopango volcanic eruption, terrace agriculture, and highland centers like Kaminaljuyú wove a dense tapestry of crisis. Scholars debate which trigger mattered most:

- Climate primacy (Gill 2000): stalagmite records show megadroughts (810–950 CE) that made agriculture impossible.

- Political failure (Demarest 2004): inscriptions at Cancuén show continued elite building during droughts, implying systemic inequity.

- Trade collapse (McKillop 2021): disrupted salt routes, traced via isotopes, triggered famine before drought struck.

All factors likely converged—with their weights varying by region. The verdict: no single cause explains the breakdown; only their interplay pushed the system to collapse.

4 | New Beginnings

The story does not end with stelae falling silent. In the Puuc region, architectural innovation flourished. The elegant Puuc‑style facades, with finely mosaicked stonework and smooth wall zones, replaced earlier mask friezes.

At Chichén Itzá, trans‑coastal trade networks and mass rituals in columned halls emerged. Later, Mayapán inherited these traditions, and highland communities reorganized—whose descendants today speak K’iche’, Kaqchikel, or Q’eqchi’.

The “long farewell” was not a conclusion but a transition to new social forms. While the southern courts faded, communities in the north and highlands preserved their culture—to this day, often under colonial and modern pressures. That millions of Maya still speak their languages and cultivate maize as their ancestors did shows that true resilience lies not in pyramids, but in knowledge about when to leave a system behind.

5 | Three Lessons from the Long Farewell

- Ecology meets economy: Climate shocks that shatter supply chains strip even the most powerful elites of their stage props.

- Inequality accelerates collapse: Rising tribute and resource centralization erode solidarity, deepening crisis.

- Transformation rather than extinction: Maya culture adapts, shifts centers, invents new rituals—languages and cosmologies endure.

But perhaps the most important lesson lies beyond archaeology—in the voices of those who carry this history today.

6 | The “Long Farewell” from Maya Perspectives

As scholars debate the term “collapse,” Maya communities tell a different story—one of conscious departure, resistance to oppressive structures, and invisible continuities missed when one stares only at stone.

Archaeologists mark the stelae’s end as a “collapse,” but Maya descendants—today some seven million people in Mexico and Guatemala—see the transformation not as failure, but as resilience in action.

6.1 Oral Traditions

The Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’-Maya, recounts three unsuccessful “prototype races.” The second—wooden humans—perish due to arrogance and disrespect for the living world. In Tedlock’s 1996 translation (p. 42–43), it states:

“Again came humiliation, destruction, and annihilation … A mighty flood showered upon the heads of the manikins, the wooden people … Everything spoke: their water jars, their tortilla plates, their pots, their dogs, their grinding stones … ‘You tormented us, you devoured us; now we shall devour you … We shall crush and grind your flesh,’ said the grinding stones.”

This episode links hubris (wooden humans forgetting the “heart of the sky”) with ecological violation: nature and everyday objects revolt because they were exploited. That moral lesson—abuse resources, and you destroy yourself—echoes real-world Maya declines, where deforestation and soil depletion undermined kingdoms.

Likewise, the Chilam Balam texts from Yucatán describe urban abandonment not as failure but as a cyclic transition: after a “Stone era” ends, the “Grace of Maize” begins—symbolizing rebirth and renewal.

6.2 What Does This Past Mean for Today?

Contemporary Maya heritage-keepers fight—against land dispossession, climate change, and cultural erasure. While archaeologists mark the end of stelae as “collapse,” central elements of Maya life persist:

- Agriculture: Milpa agroforestry systems, practiced for over 3,000 years, remain more sustainable than most modern monocultures.

- Spiritual life: Rain rituals to Chaac still take place, often intertwined with Christian holy days.

- Languages: Over 30 Maya languages have endured colonialism and globalization.

6.3 Lessons for the Present

Thus, the “long farewell” was neither triumph nor tragedy, but a compass. It shows that “collapse” is always a matter of perspective—and can sometimes mark the beginning of something new.

Modern Maya intellectuals, like the Jakaltek writer Victor Montejo (Jakaltek/Popti’, from Huehuetenango, Guatemala), stress: It wasn’t “the Maya” who collapsed—but systems that confined them. In Maya Intellectual Renaissance (2003, p. 145), he writes (roughly):

“The lesson of the past is not that people fail, but that systems which oppress them fail; the answer lies in autonomy, not ‘progress’ at any cost.”

This position links archaeological transformation with current debates on indigenous self‑determination, land rights, and sustainable development.

As today’s challenges show, Maya “collapse” invites reflection: crises arise when elites ignore warning signals—be it drought, trade disruption, or social fragmentation.

Further Reading

- Demarest, Arthur A. (2004): Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Cambridge University Press. A comprehensive political‑ecological account of the Classic Maya demise.

- Kennett, Douglas J., et al. (2012): Development and Disintegration of Maya Political Systems in Response to Climate Change, Science, 338(6108), 788–791. A foundational study linking drought records with sociopolitical breakdown.

- Restall, Matthew & Solari, Amara (2011): 2012 and the End of the World: The Western Roots of the Maya Apocalypse. A critical examination of Western misconceptions and indigenous cultural continuity.

- Graeber, David & Wengrow, David (2021): The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Challenges traditional “collapse” narratives to imagine alternative social transformations—relevant for Maya studies too.